Hidden in the Archives ~ C18th & C19th Heirloom Textiles

of

Auckland Museum Tàmaki Paenga Hira, New Zealand

[Thank you, Auckland Museum, for Research Access to Artefacts & Images]

Theorising a New Methodology: Recording Historical Costume Pattern Drafts

Research By Anna Deacon, New Zealand. 2022-2024

ORCID Ref: 0009-0003-6386-4367

Copyright of anna@annadeacon.com, please email for Permissions to Cite

My connection with Auckland Museum began in early 2022 while researching a selection of garments for two film projects with an 18th-century aesthetic. As a Lead Costume Pattern Drafter for film and television, the opportunity to undertake primary construction research is invaluable for context and accuracy. By mid-2022, enthused from this research, I undertook a Master’s in Historical Costume, reinvigorating a passion for research and the elegant purity of historical construction methods that got me into the costume business 28 years ago.

Inspired by the initial artifact observations, my study thesis became Hidden in the Archives: Heirloom Textiles of Tamaki Paenga Hira Auckland War Memorial Museum. Traditional research methodologies place value on printed sources, but the garments themselves can reveal so much. Their cut, construction, materiality, and even wear patterns can provide unique insights into the past that printed sources can not reveal. My passion is pattern drafting, creating the ‘blueprints’ from which a garment is constructed, so naturally, my thesis methodology for understanding these heirloom garments developed from drawing upon various historical practices and integrating them with creative modern technologies to theorise my unique, innovative and experimental process to ascertain precise garment textile patterns from the artefacts. The direction of the approach is quite different from that of creating something new, as the additional challenge is trying to faithfully and aesthetically match the peculiarities of the original with its distinctive evolution. Of course, the authenticity of a recreation is a misnomer, as only the original can be authentic; the recreations through P.A.R. [Participatory Action Research] are instead a verisimilitude, testing specific working theories and not an attempt to make a ‘pretty garment’ to wear.

As with the McCall dress, and indeed many artefacts, the methods for recording details need to be ‘creatively’ documented due to the fragility of the textiles. They are too delicate to be opened up to take measurements or manipulated to ‘straighten out’. Therefore, observational research requires creative thinking to ensure the safety of these compromised objects to ‘deconstruct’ the garment by logical, unintrusive methods to reverse engineer construction and record the garment’s original pattern [flat pieces] and subsequential alterations. Modern technologies such as X-radiography, photogrammetry, and digital re-creation all offer immense potential as applications for research into historical garments, providing a way to ‘see’ into aspects of a garment not possible due to construction methods, or so small the human eye is unable to register. However, these technologies are rarely accessible even within more prominent museums, let alone to an independent researcher like myself.

One traditional technique used as a control methodology with the plain woven garments in the Milward and Panuwell collections is where the material weave is used as a guide / or grid to follow. Allowing the tape measures to follow the undulations of the fabric, laying one following a ‘warp’ [vertical] thread and a second across the weft [horizontal] threads at incremental or pivotal sections, recording positions and measurements upon a diagram. Although effective, this method can lead to inaccuracies in measurements when areas of the garment are inaccessible or laboriously manipulated. It is also open to a biased aesthetic where the drafter is naturally influenced to ‘balance’ the measurements and drafting line to follow a known norm.

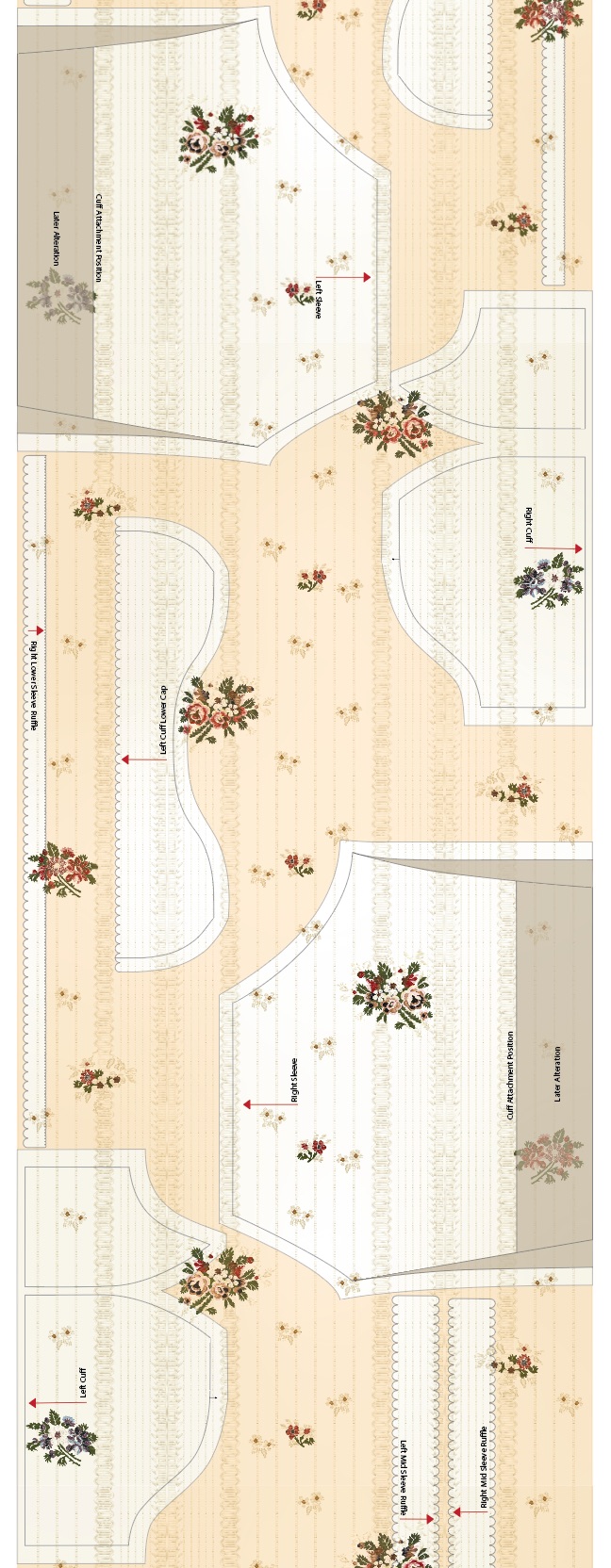

By contrast, I have developed an experimental approach by creating 100% accurate fabric weave design recreations, upon which the garment panel pieces are mapped out as they would be flat and unconstructed. This is achieved by recording the placement of weave design elements and how they are interrupted within the garment seams, edges and details. Due to this method being entirely visual, handling is minimal; accuracy is precise and authentic, with drafting curves remaining true. Three case studies were selected, case study 1- McCall [AM T64], case study 2 – Richardson / Davidson [AM col.0791] and case study 3 – Brookes [AM T696] dresses. All have been subject to alterations and repurposing over the centuries, but are constructed from 18th-century silk brocaded surface designs with relevant consistency within the weave and unique identifying weave details close enough together to establish accurate garment panel pattern drafting. Additionally, these pattern pieces can then be placed like a jigsaw upon a length of the weave design to ascertain a realistic approximation of the pattern piece lay, understanding the efficiency of how the material was used and the yield required. This new methodology for documenting textile artefacts and their garment drafting patterns has proven exceptionally successful, a process even those without drafting experience could execute.

By valuing tacit knowledge and practical theory as legitimate forms of research, P.A.R. plays a crucial role in building a complete picture of the garment’s history and its connection to its original milieu, in conjunction with its known provenance and cultural context. This comprehensive approach is instrumental in understanding the full story behind each garment.

Winning the Geoffrey Squire Memorial Bursary 2023 [GSMB] from the Costume & Textile Association U.K. [C&TA] made an expediential contribution to testing and realising these methodologies.

After detailed photography of the visible areas of the outside and interior of the gown and armed with a ruler for measuring the design-element scale, I digitally recreated the weave design in Adobe Illustrator. The recreated design was printed onto transparent acetate sheets, then laid onto the flatter skirt sections and meticulously checked for placement and scale of the design repeat and motifs. With the fabric recreation confirmed, the edges and seam lines as they cut through the weave design are mapped, essentially drafting the garment panels.

Richardson / Davidson drafting process

My methodology provides valuable insight into the yield used, what percentage would have been wasted, and significant areas that may have been utilised for additional adornments, such as ruffles or puff edgings, which no longer survive. These insights are not possible with other reverse engineering drafting methods. Note that waste was minimal with such expensive fabrics in the 18th century, it is assumed pieces were placed with the best fit, as not necessarily placed directionally; however, the McCall dress demonstrates concerted decisions of design placement to provide an aesthetic balance on the sleeves, front bodice and back waistline, another example of wealth and grandeur.

McCall ~ Considered design placement

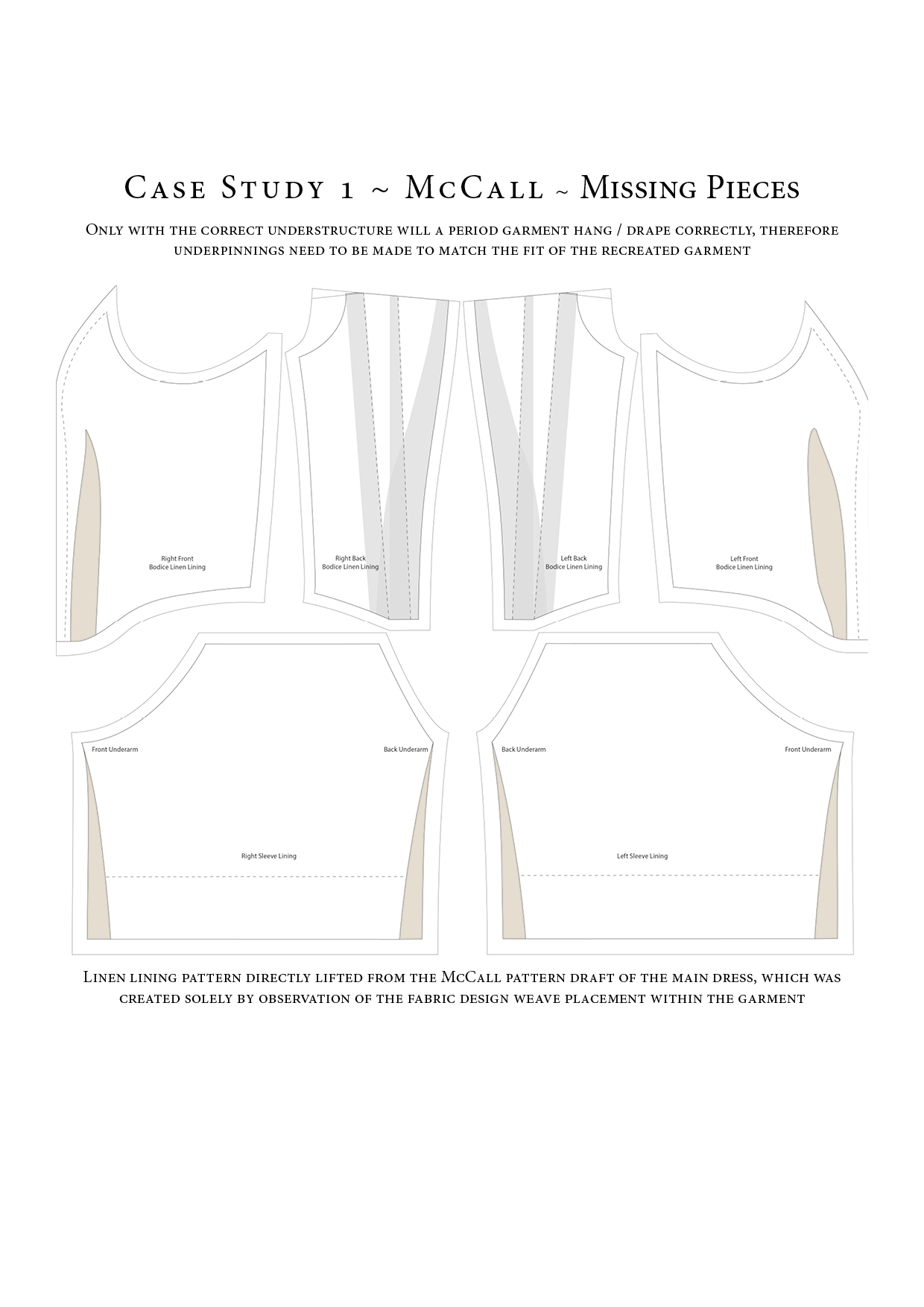

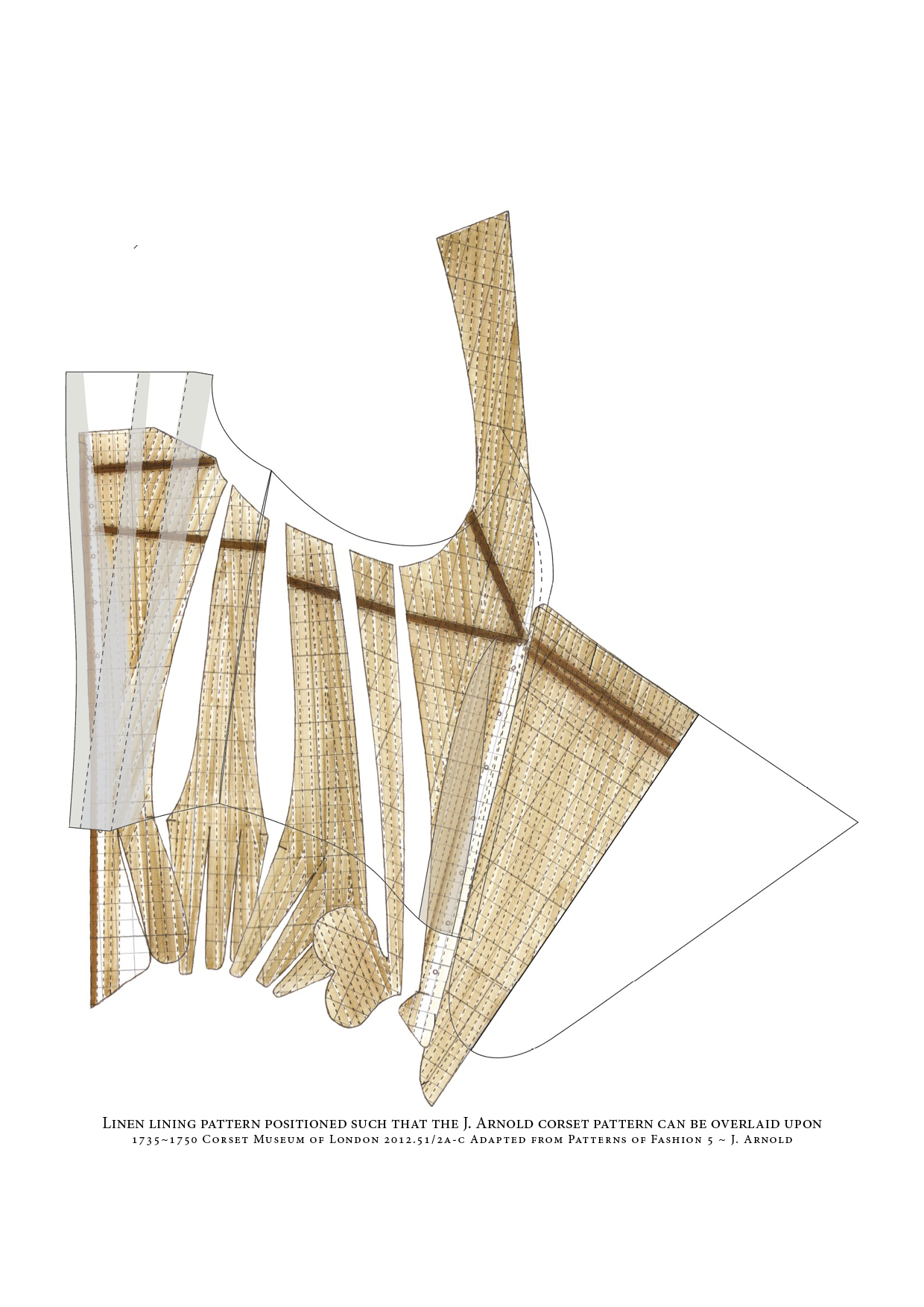

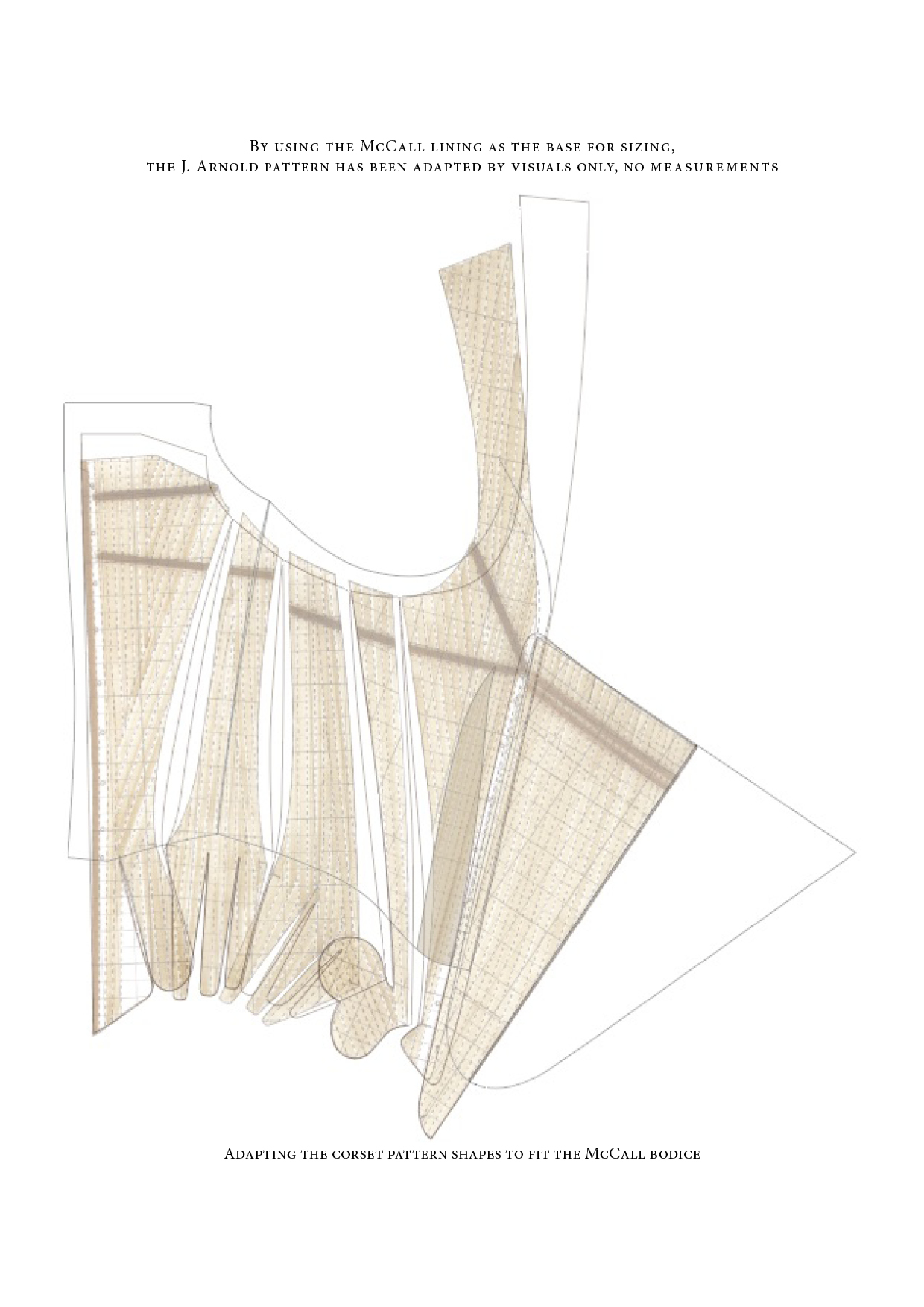

The required yield of the recreated fabric was then printed on cotton on a large-format digital printer to check the accuracy of the drafting theory by creating a toile using the drafted patterns. The outcome of this research approach has proved very successful; utilising the weave design to inform precise placement, size, and angles of folds and seams results in a more accurate recreation than measurements alone could achieve. The toile also served an additional purpose; the original dress was far too fragile to put on a mannequin to compare the hang and design alterations. This is where the accurately recreated toile can play an informative function, by mounting the toile on a mannequin with the appropriate period undergarments finally these can be ascertained, learning more about the wearer’s size and better understand the fit and movement of the garment.

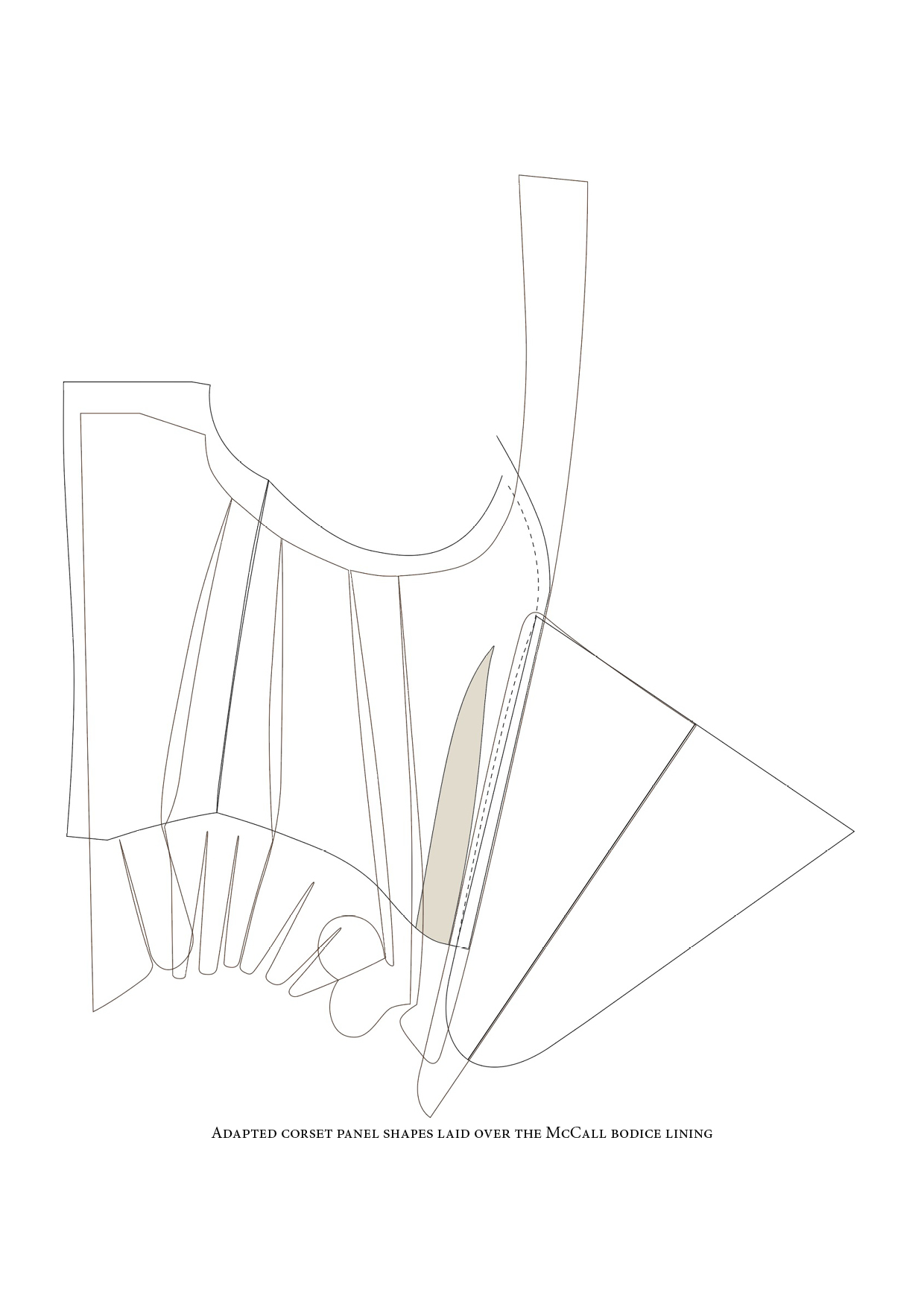

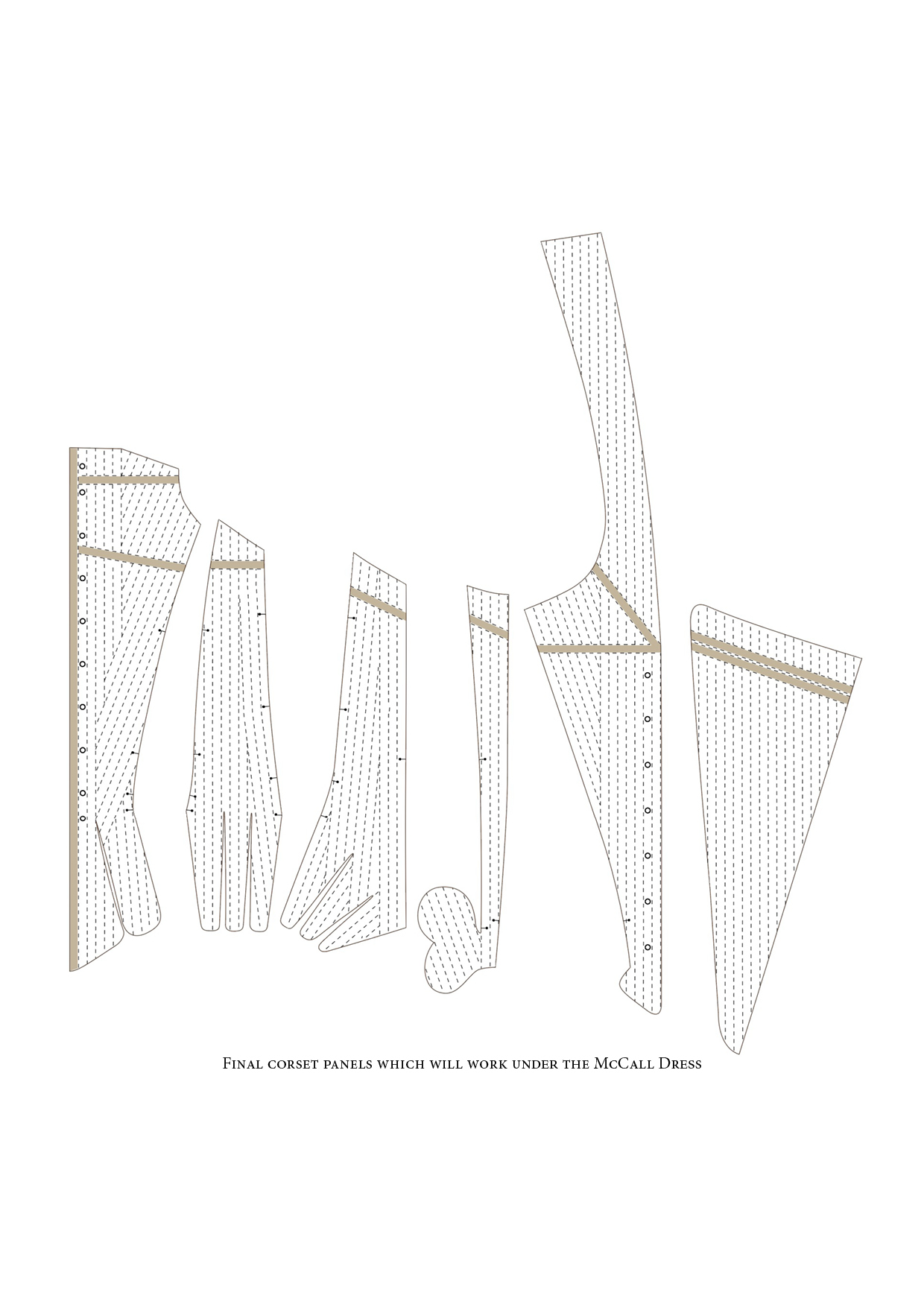

McCall ~ Reverse Engineering drafted patterns to create fit-perfect missing undergarments

The decision to use calico rather than silk was not because of cost alone, for there was no way to reproduce the fabric accurately. We no longer have the narrow hand-draw loom setups, let alone the tacit knowledge of the weavers who were experts in their crafts. Additionally, as previously mentioned, the purpose was not to create pretty costume reproductions, but toiles, to ascertain the accuracy of the theorised drafting method.

Case Study 1: Helen McCall Wedding Dress

Auckland Museum T64

Case Study 2: Richardson / Davidson Dress

Auckland Museum col.0791

Case Study 3: Brookes

Auckland Museum T696